A Transformation in Our Relationship with Truth

Our relationship with truth today seems profoundly transformed. In an era when information circulates at lightning speed, doubt becomes reflexive, facts are contested, mistrust toward journalists and scientists grows, and false information multiplies. This crisis of truth, widely discussed for several years, even has a name: post-truth.

In 2016, the Oxford Dictionary chose “post-truth” as its Word of the Year. It is defined as “circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

When Facts Are No Longer Enough

This shift is felt everywhere: in public debates, on social media, in everyday conversations. It is no longer about debating what is true or false, but about adhering to narratives based on how we feel or what we want to believe. We no longer seek to compare arguments, listen to others, or build a shared understanding of reality. We either embrace or reject, in a binary manner.

In the era of post-truth, facts are no longer sufficient. What matters is the effect they produce on us. Information that triggers anger, outrage, or fear is far more likely to be shared — and believed — than neutral, cold, or overly complex information. Emotion prevails over reason.

This was evident, for example, during the Covid-19 pandemic. Faced with a novel virus, scientific uncertainty was quickly filled by reassuring beliefs or simple conspiracy narratives. Messages such as “vaccines contain microchips” or “the media is hiding the truth” spread at lightning speed. Why? Because they addressed an emotional need: the need for immediate explanation, to identify a culprit, to feel on the “right side.”

Cognitive Biases… Amplified by Algorithms

Our brains love shortcuts. They prefer what confirms what we already think (confirmation bias), what is repeated often (illusion of truth), or what everyone shares (popularity bias). These mental mechanisms, inherited from our evolution, push us to favor familiar, comfortable, or emotionally charged narratives, even if they are false.

Social media algorithms amplify these flaws. They trap us in information bubbles where we only see content that resembles us or provokes a reaction. The result: our certainties are reinforced, and contradiction becomes the enemy.

The Effect of Information Overload: Truth Drowned in an Ocean of Trivia

The era of post-truth is not only characterized by the manipulation of facts but also by a phenomenon that makes the quest for truth even more complex: information overload. We are now confronted with a constant flood of information, sometimes insignificant, contradictory, or unreliable.

Aldous Huxley, in Brave New World, expressed this concern by warning that truth would not be banned but drowned in a sea of irrelevant information. This saturation makes the search for meaning even more difficult in a world saturated with content.

In this hyperconnected world, citizens are overwhelmed by information, but few of these pieces are truly meaningful. Superficial discourse, fake news, and omnipresent advertising make the work of discernment even more arduous.

The Manufacture of Doubt: A Well-Honed Strategy

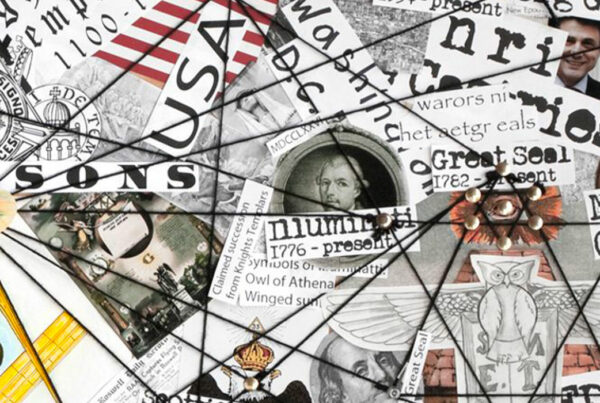

The concept of post-truth is not merely informational chaos. It is also part of a deliberate strategy to blur reality. As early as the 1950s, the tobacco industry hired experts to cast doubt on the dangers of smoking. This method was later reused by oil lobbies to deny global warming. Rather than refuting facts, the goal is to weaken their impact, to blur the boundary between truth and falsehood. Doubt becomes a weapon.

Post-Truth and Politics: A Mutation of Lies

Since antiquity, thinkers have questioned the role of lies in politics. Plato already distrusted orators skilled at manipulating crowds. Machiavelli, later, asserted that a good prince must know how to be “both fox and lion” — in other words, to deceive as much as to dominate. But in the era of post-truth, something has changed. The lie is no longer a hidden tactic: it is affirmed, repeated, embraced. As philosopher Olivier Abel explains, we have moved from strategic lying to “performative lying,” which acts faster than truth.

George Orwell, in 1984, describes a world where the past is continually falsified to control the present, thereby annihilating the possibility of a common reality. In this context, it is not merely about lying, but about destroying the possibility of agreement on a shared reality.

Hannah Arendt, in Truth and Politics, warned that “facts are not safe in the hands of power.” The danger, according to her, lies not only in the manipulations of the powerful but also in our own tendency to twist facts to fit our beliefs. Truth thus becomes malleable, not only for those who govern but also for those who are governed.

This dynamic has also fueled the rise of certain populist leaders. Donald Trump, for example, popularized the use of “alternative facts” or “truthful hyperboles”: spectacular exaggerations that seduce, even when manifestly false. The goal was not to convince through rigorous argumentation, but to reinforce the emotional allegiance of his electorate. It was no longer about telling the truth, but about speaking an emotional and identity-based language that flattered the preexisting convictions of his camp.

These reflections remind us that, in a political context, the manipulation of facts is not limited to lies alone, but also includes how these lies are integrated and accepted by society. Truth becomes increasingly relative, and democratic debate, grounded in shared facts, is profoundly disrupted.

Can Democracy Survive Without Truth?

Truth is not merely a moral ideal. It is an essential political condition for building a common world. If everyone holds their own version of the facts, then debate becomes impossible. The post-truth regime transforms discussion into a clash of irreconcilable narratives, where the goal is no longer to understand, but to convince one’s own camp — even at the cost of delegitimizing the other.

“Truth is not merely a moral ideal; it is a political condition for the possibility of a common world.”

– Myriam Revault d’Allonnes

In this context, truth becomes not only relative but incidental. This shift weakens trust in institutions, media, and experts. And without this minimal trust, democracy falters.

Fact-Checking: A Fragile Rampart

Fact-checking has emerged as a fragile but necessary rampart. As early as 2000, initiatives like Hoaxbuster paved the way for online fact verification. They were quickly joined by numerous journalistic outlets worldwide, making fact-checking a key tool in the fight against disinformation. But while the effort is commendable, it is insufficient to reverse the trend: false information spreads faster than corrections, and those corrections struggle to convince people whose beliefs are already deeply entrenched.

Fact-checking alone cannot stem this phenomenon as long as the root causes persist: a platform business model based on virality rather than veracity, growing distrust of media and institutions, and a generalized blurring between knowledge, opinion, and belief.

In this context, relearning how to inform oneself, to doubt one’s certainties, to verify sources, and to confront different viewpoints becomes almost a political act. Resisting the era of post-truth means affirming that facts still matter — and that they remain the minimal condition for any democratic debate worthy of the name.