Long relegated to the margins, conspiratorial thinking has established itself as one of the most persistent phenomena in contemporary history. Far from disappearing with reason, it develops in increasingly rationalized societies. From the 18th to the 21st century, it accompanies the rise of revolutions, the politicization of the masses, crises, and authoritarian regimes.

Conspiratorial thinking thus appears as a paradoxical construction: both mythical and modern, irrational yet structured, it offers a reading of the world where nothing is due to chance and where major events become the result of hidden wills. In a complex world, it is a promise of clarity.

Modernity and conspiracy: Two interpretations of the phenomenon

Researchers have proposed two major approaches to understanding the inscription of conspiracy in modernity.

- The first, called the continuist thesis, (Karl Popper or Norman Cohn).

It considers conspiracy theories as a secularization of ancient religious myths and collective superstitions. Where once the intervention of deities or occult forces was invoked, we now speak of “secret societies,” “hidden elites,” or “powers in the shadows.” It is therefore a form of archaicism adapted to contemporary codes.

- The second, referred to as an anthropological novelty (François Furet).

It asserts that conspiratorial thinking was born with democratic modernity itself. In an era where history is believed to be shaped by human will, the need to designate hidden authors becomes a response to political uncertainties. Conspiracy thus emerges in a rationalized world, yet still eager for narratives and coherence.

Conspiracy theories throughout history

These two frameworks of interpretation find echoes in concrete history: conspiratorial thinking adapts to fears and major political, social, or technological upheavals.

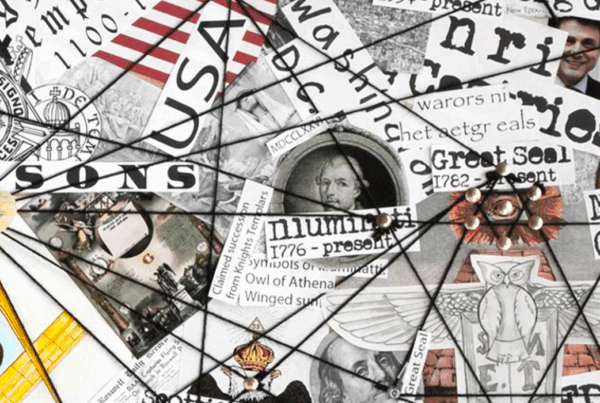

✒️ 18th century – Illuminati and Freemasons

With the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, the first major global conspiracy theories emerge. Groups like the Illuminati or Freemasons are accused of orchestrating the fall of the Ancien Régime. These narratives mix anticlericalism, esotericism, and political fantasies. It marks the beginning of a structured conspiratorial thinking, aimed at explaining the upheavals of the established order through invisible hands.

🧊 20th century – Cold War, JFK, and state paranoia

The 20th century becomes a factory of conspiratorial narratives. The fear of communism fuels the idea of a global infiltration. Intelligence agencies like the CIA are perceived as all-powerful entities. The assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 crystallizes this mistrust: for many, it is impossible that a lone gunman could trigger such a political earthquake. Multiple versions circulate – mafia, intelligence agencies, Cold War – illustrating an era haunted by suspicion.

🌐 21st century – Internet, Covid, and QAnon

With the digital explosion, conspiratorial thinking becomes global, instantaneous, viral. The post-September 11, 2001 era sees the rise of theories claiming the attacks were an “inside job,” orchestrated by the U.S. government. The Covid-19 pandemic marks another turning point: virus created in a lab, microchips in vaccines, 5G antennas… These narratives self-perpetuate on social media, sometimes promoted by influencers or media figures. The QAnon movement pushes the logic to the extreme, with the idea of a global pedosatanic conspiracy led by a political elite that only Donald Trump could overthrow.

The example of the “Jewish conspiracy,” the basis for a lasting fantasy

Among the most influential narratives, the myth of the Jewish conspiracy stands as an emblematic example of this dynamic. This narrative takes root as early as the Middle Ages, with accusations of poisoning wells, and extends into the 20th century with the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a forged document presenting an alleged strategy of world domination by Jews. This narrative would later also fuel Nazi ideology and continue to circulate into the 21st century.

This myth demonstrates how these narratives can combine the continuity of stereotypes with contextual adaptability. It serves several functions: cognitive (it provides a key to understanding the world), practical (it mobilizes followers), and political (it justifies hatred or exclusion).

Myth, still alive in our rational societies

Conspiracy narratives fit within a mythical logic, in the anthropological sense of the term. Even in modern societies, these myths do not disappear: they recompose meaning from ancient materials, in a temporality suspended between past and present. They are narrative responses to crises, attempts to explain the loss of bearings.

Conspiracy thinking thrives particularly in moments of instability: health crises, political upheavals, profound social transformations. It returns as an attempt to rebuild coherence where reality seems chaotic or senseless.

A transformed imagination of power

What distinguishes modern conspiracy theories from their earlier versions is that they are based on a very particular conception of power. It is no longer about hereditary or divine power, but about human, technocratic, impersonal, and above all, invisible power. A power infiltrable, manipulable, that must be unmasked or overthrown.

Within this logic, no event is left to chance. Everything is orchestrated behind the scenes by elites or hidden entities. Conspiracy thinking thus offers a totalizing reading of history, where the unforeseen, the collective, or the accidental have no place.

This way of interpreting the world fuels a paranoid vision of politics, marked by radical distrust of institutions, the media, or science. It rejects uncertainty, complexity, and contradictory debate. At its core, it expresses a need for certainty in an uncertain world – a world traversed by crises, rapid changes, and wavering landmarks.

Searching for meaning in an uncertain world

Ultimately, conspiracy thinking is not a mere remnant of ancient beliefs: it is a structured response to uncertainty, a attempt to restore coherence where everything seems blurred. This is why it appeals, even in the most educated or technologically advanced societies. It offers a global, reassuring narrative where reality imposes doubt, complexity, or chance.

Source: CNRS Éditions: Les rhétoriques de la conspiration – Emmanuelle Danblon and Loïc Nicolas (Historicizing the Imaginary of Conspiracy, pp. 43-56)

Long relegated to the margins, conspiracy thinking has established itself as one of the most persistent phenomena in contemporary history. Far from disappearing with reason, it develops within increasingly rationalized societies. From the 18th to the 21st century, it accompanies the rise of revolutions, the politicization of the masses, crises, and authoritarian regimes.

Conspiracy thinking thus appears as a paradoxical construction: both mythical and modern, irrational yet structured, it offers a reading of the world where nothing happens by chance and major events become the result of hidden wills. In a complex world, it is a promise of clarity.