Fake news did not originate with the internet. Long before social media, hoaxes, rumors, and mass manipulations already raged in streets, royal courts, newspapers, and battlefields. To disinform is not merely to tell falsehoods: it is to steer, distort, conceal, or exaggerate — in service of an interest, a power, or a belief. A brief dive into the long history of disinformation.

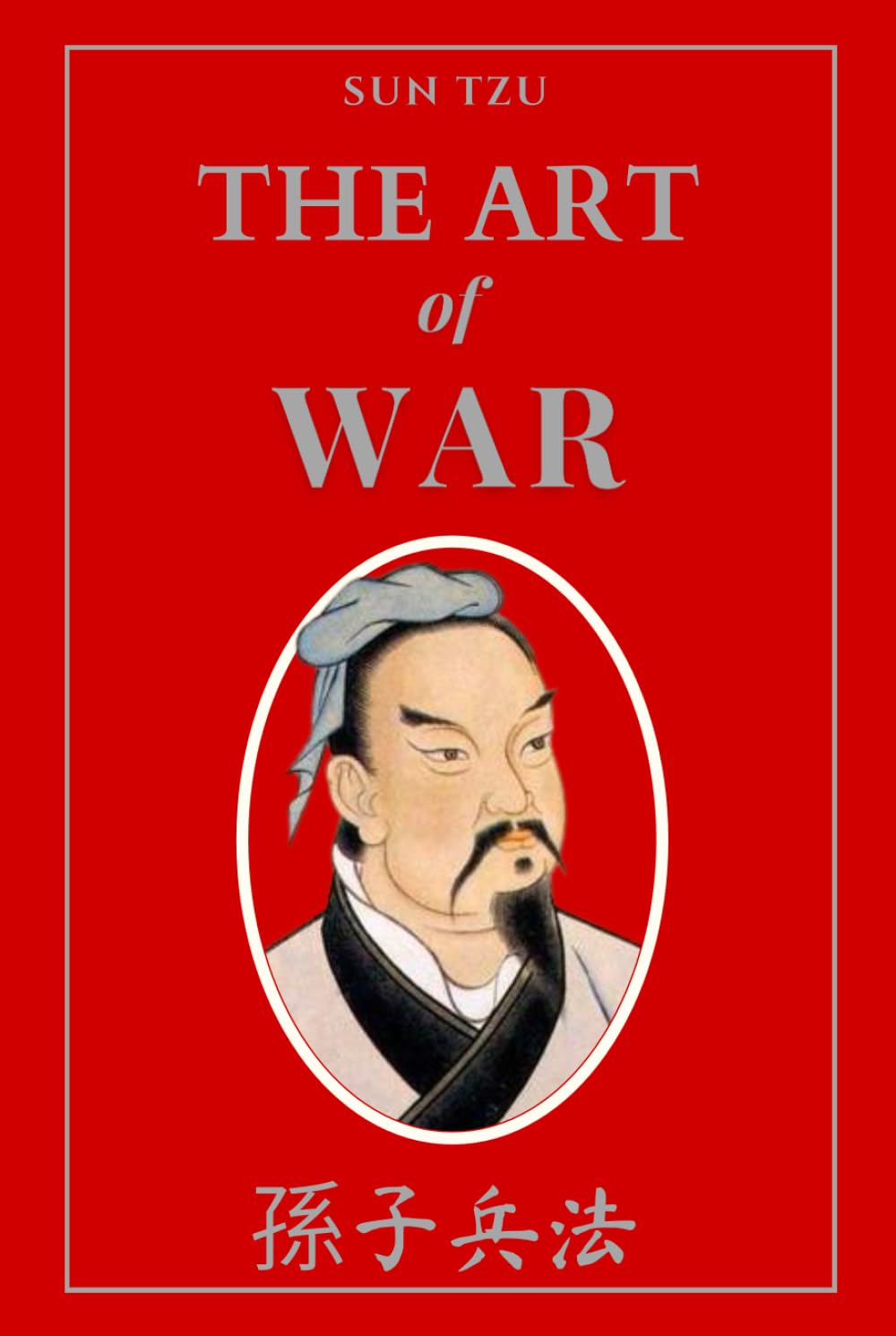

Disinformation: A Weapon as Old as War

As early as Antiquity, information manipulation was a strategic tool. The Chinese general Sun Tzu, in The Art of War (4th century BCE), already advised sowing false information to deceive the enemy.

Three centuries later, Julius Caesar wrote The Gallic Wars, a self-glorifying propaganda narrative, riddled with exaggerations, portraying him as the hero of military campaigns that were sometimes questionable. It is not merely a historical text — it is also a formidable political communication tool.

(Royer, Lionel: Vercingetorix Throws Down His Arms at the Feet of Caesar)

The Middle Ages: Rumor as Media

Before the printing press, rumor was the primary vector of information… and disinformation. In a society plagued by fears (war, famine, plague), no social group was spared — whether as an expression of popular political consciousness or a weapon wielded by the powerful. Elites used it to consolidate authority, while the people used it to voice anxieties and demands. From witchcraft accusations to scapegoats designated during epidemics, rumors sometimes fueled mass violence — and were often impossible to refute.

(Honoré Daumier: Crispin and Scapin)

The Written Word Revolution: A Turning Point

At this time, the construction of truth through writing reached a turning point. Medieval societies, from the Carolingian era to the 14th century, were transformed by the revolution of the written word. Falsification became a strategic tool in political and religious affairs. Only gradually did the concept of falsehood — as an intentional act of concealment to obtain rights and advantages to which one is not entitled — become established. Medieval thinkers inherited from Antiquity a nuanced conception of truth. Between fabula (fiction) and factum (fact), they recovered from Antiquity the concept of argumentum: what is plausible, probable, usable — without strict concern for truth or falsehood. These blurred distinctions between truth and fiction paved the way for information manipulations we still encounter today in the digital world.

(Jean Méliot, scribe and translator, 1455)

The Printing Press: The Era of Pamphlets and Fake Scoops

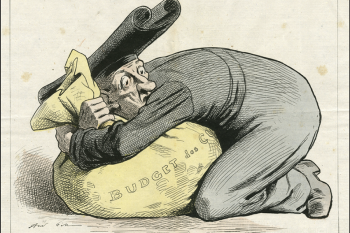

With the printing press, fake news gained speed and scale. From the 16th century onward, Europe’s religious wars were accompanied by anonymous libels (satirical, defamatory writings), fierce caricatures, and fake documents designed to demonize the enemy. Public opinion became a strategic target.

(“The Jesuit Seizing the Nation’s Wealth” – Gill’s caricature, 1878, in the newspaper “La Lune Rousse.”)

A famous example: the Monita Secreta, purported secret instructions from the Jesuits on how to acquire power and wealth, revealed in the 17th century. This forged document, permanently embedded in popular culture and collective imagination, fueled conspiracy fantasies far beyond its time, well into the 19th and 20th centuries.

19th Century: The Golden Age of Media Hoaxes

The emerging mass press loved sensational stories. In 1835, The Sun in New York published a series of articles claiming an astronomer had observed humanoid bats on the Moon. The Great Moon Hoax captivated the public before being revealed as a hoax… but the newspaper had already made its fortune. At the same time, fake scoops, court gossip, and baseless accusations spread at the speed of ink. Truth often came second to sensationalism.

20th Century: State Propaganda and Psychological Warfare

The two World Wars witnessed the rise of industrial-scale disinformation. Posters, films, radio: states orchestrated vast campaigns to support the war effort, demoralize the enemy, or justify crimes.

In 1903, Russian secret services published The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an antisemitic forgery purporting to reveal a global Jewish conspiracy. This deceitful text, rooted in a long tradition of false accusations, would fuel Nazi ideology and be disseminated into the 21st century.

During World War I, the British spread horrific tales about German soldiers (mutilated Belgian babies, rapes, invented atrocities) to rally public opinion and justify engagement in the conflict. These “atrocity propaganda” campaigns were later criticized for their fabrications.

The Nazis, meanwhile, used radio as a mass weapon. Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda, controlled the airwaves, newspapers, and cinema to construct a false narrative glorifying the regime and demonizing its enemies. The film Jew Süss (1940), for example, was a powerfully effective antisemitic propaganda tool.

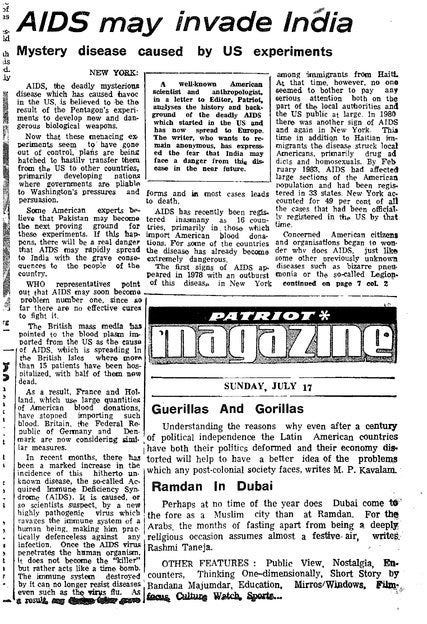

During the Cold War, the CIA and the KGB competed in disinformation operations. One of the most famous was Operation INFEKTION, carried out by the KGB in the 1980s: it aimed to make people believe that AIDS had been created by the United States in a military laboratory for biological warfare purposes. This rumor was picked up by numerous media outlets worldwide.

(The original article published in the Indian “Patriot” Magazine. July 1983.)

The United States itself practiced large-scale disinformation: during the Vietnam War, it deliberately concealed certain casualty figures and falsified military reports. This system was exposed in 1971 with the publication of the Pentagon Papers, revealing the extent of state deception.

The Digital Age: The Virality of Falsehood

With the internet, fake news entered a new dimension. Now, anyone can produce and disseminate information, without filters. Rumors become viral, conspiracy theories find their audience in a few clicks. The Covid-19 crisis, the 2016 U.S. elections, and recent armed conflicts have become fertile ground for disinformation, blending manipulated videos, fake experts, emotional edits, and automated bots. Disinformation is no longer reserved for the powerful: it spreads through WhatsApp groups, TikTok videos, and tweets.

A Constant in History: To Believe, Simplify, Accuse

Why do fake news succeed? Because they rely on ancient cognitive mechanisms: our need to believe, to understand quickly, to designate a culprit. Whether to legitimize a war, rally a cause, or sell newspapers, disinformation flatters our biases, our fears, our need for meaning. It evolves with technology, but its deep mechanisms remain the same.

Learning to Read Between the Lines

History shows us: disinformation is nothing new. It changes form and medium, but always relies on the same mechanisms. Faced with the avalanche of content and the speed at which information circulates, developing critical thinking remains essential. Verify, compare, doubt: these are reflexes to cultivate. We may not be able to eliminate fake news, but we can learn to better defend ourselves against them.