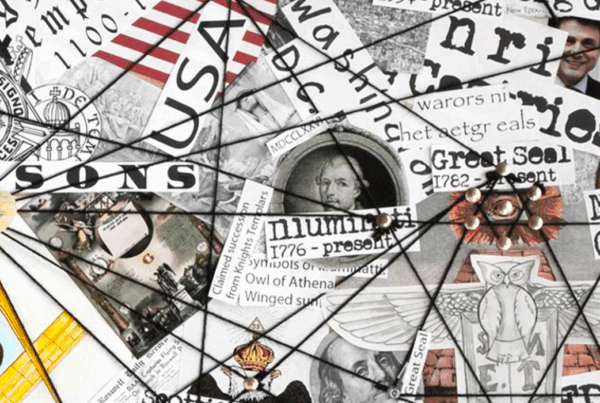

Conspiracy theories do not rely solely on an idea: they are built upon a well-honed rhetoric, composed of multiple arguments, effective persuasion strategies, and methods that make debate difficult. Even though the narratives change, we often find the same argumentation techniques. Knowing them better is the best way to protect ourselves against them.

1- Argument Stacking: The “Argumentative Mille-Feuille”

One of the most common tactics in conspiratorial discourse is what is called the “argumentative mille-feuille”. This is not a logical, structured argument, but rather an overload of data, arguments, technical or scientific details. Each one taken separately may seem harmless or even erroneous, but their accumulation creates an impression of solidity.

Moreover, these arguments often draw from complex fields: biology, climate science, geopolitics, mathematics… They give the impression that “everything fits together,” that a vast plan is revealed to those who know how to read it.

👉 Example: When someone claims vaccines are dangerous, they will cite suspicious patents, conflicts of interest, misinterpreted study excerpts, testimonies from dissident doctors, and poorly contextualized statistics… Faced with such a pile, it’s difficult to deconstruct everything point by point.

2- An Antagonist Posture: “Those Who Know” vs. “The Sheep”

Conspiratorial discourse often relies on a strong symbolic divide: on one side, “those who know”, the “awakened,” those who see through the manipulation. On the other, “the sheep,” the masses who swallow everything without thinking. Adhering to a conspiracy theory thus becomes a marker of intelligence or lucidity.

👉 This rhetoric plays on identity: one doesn’t believe in a theory just for what it says, but for what it says about oneself. Rejecting it would mean being naive or complicit. The argument is no longer “I am right,” but “I am not fooled.”

3- Inversion of Doubt: From Critical Citizen to Vigilante

Another central element: the rhetoric of the engaged citizen resisting a generalized lie. Normally, when a lie is suspected, one seeks evidence. But in conspiratorial discourse, the logic is inverted: one starts from the premise that there is a liar, and then seeks evidence.

This creates a posture of moral quest: one becomes a resistor, a lone investigator against the powerful. This can be empowering, but it often prevents questioning the theory itself.

👉 Example: If someone claims the Earth is flat, they start from the assumption that NASA or scientists in general are lying. Anything supporting a spherical Earth is seen as manipulation. The goal is no longer to seek truth, but to unmask the presumed lie.

4- Irony and Sarcasm: Tools of Disqualification

Conspiratorial rhetoric also uses powerful emotional tools, such as irony, mockery, or a condescending tone. Those who doubt the theory are ridiculed, implying that one would have to be blind or stupid not to see “the truth.”

This strategy allows anticipation of criticism: if you don’t believe the theory, you’re a “sheep,” “asleep,” or “a sellout.” It’s no longer a debate, but a game of disqualification. And who would want to be seen as a sheep refusing the obvious!

Why Is It Effective?

These strategies have one thing in common: they lock down the discussion. Every criticism is absorbed as proof of the conspiracy. Every contrary fact is disqualified. And every person who doubts is suspected of being part of the system. This makes refutation almost impossible.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t do anything. Understanding these mechanisms, recognizing them, talking about them — this is already a first step to maintaining critical thinking without falling into hostility.

To Be Continued…

In a future article, we will explore why some people are more susceptible to conspiracy theories: the role of emotions, distrust, feelings of exclusion… The goal is not to judge, but to understand the social, psychological, and digital mechanisms that make these narratives so appealing.

Sources: https://theoriesducomplot.be/